This blog shall continue in the secular ( not spiritual) methodology. The New Yorker, yet again, came to my rescue and inspired me. But even prior to this inspiration, do have to admit that I am an advocate of storytelling. Storytelling is a proven method of getting people’s attention, often (when they are not looking) sneaking in a moral to the story, a gem of truth, occasionally some spirituality. Therefore. Parul Sehgal’s “Tell No Tales: Storytelling has been sold as a solution to everything. But it comes at a cost” grabbed my attention. The beginning paragraph immediately grabbed my attention.

“After a millennium, she remains the hardest-working woman in literature. It was not enough to be saddled with a husband who had the nasty habit of marrying and murdering a new virgin every day to assure himself of spousal fidelity. Nor was it enough to produce a series of nested stories under such deadlines (truly, I complain too much), stories so prickly and tantalizing that the king postponed her murder every night to wait for the next installment. That’s to say nothing of the entirely forgotten three children she bore over those thousand and one nights. Who recalls that there was always a new baby in Scheherazade’s arms?

Scheherazade has earned her rest, but she remains booked and busy, obsessively renamed and reclaimed. She is dusted off and wheeled out wherever the “magic of storytelling” is conjured, irresistible to any writer trafficking in “wonder” or “enchantment.” Her ghost floats through the work of Dave Eggers, Colum McCann, and Salman Rushdie in strenuous if harmless homage. But she has also been claimed by new constituencies and put to unsavory new uses. The narrator of “The Arabian Nights” must find herself bewildered at being name-checked in Karl Rove’s “Scheherazade Strategy,” as well as in articles about brand management, serialized content, mastering the attention economy—the unwitting inspiration, and occasional face, of the shifty and shifting tangle of alibis that goes by “storytelling.”

After capturing our attention, (noble story-telling at its best) , Sehgal continues, defining her terms. (I wonder who else might do this? Could it be me?)

“Do we dare define it? “Storytelling”—as presently, promiscuously deployed—comprises fiction (but also nonfiction). It is the realm of playful fantasy (but also the very mortar of identity and community); it traps (and liberates); it defines (and obscures). Perhaps the most reliable marker is that little halo it has taken to holding above its own head, its insistent aura of piety. Storytelling is what will save the kingdom; we are all Scheherazade now. Among the other entities storytelling has recently been touted to save: wildlife, water, conservatism, your business, our streets, newspapers, medicine, the movies, San Francisco, and meaning itself. Story is our mother tongue, the argument runs. For the sake of comprehension and care, we must be spoken to in story. Story has elbowed out everything else, from the lyric to the logical argument, even the straightforward news dispatch. In 2020, the Times’ media columnist wrote that the publication was evolving “from the stodgy paper of record into a juicy collection of great narratives.”

Do love Sehgal’s use of language – story is the mother tongue, elbowing out everything – lyric, logical argument, news despatch, describing storytelling as juicy. Sehgal now analyzes the ‘why’ of the storytelling phenomena.

“All sorts of studies are fanned out in defense: we are persuaded more by story than by statistics; we recall facts longer if they are embedded in narrative; stories boost production of cortisol (encouraging attentiveness) and oxytocin (encouraging connection). We are pattern-seeking, meaning-making creatures, who project our narrative needs upon the world. “Homo sapiens is a storytelling animal that thinks in stories rather than in numbers or graphs, and believes that the universe itself works like a story, replete with heroes and villains, conflicts and resolutions, climaxes and happy endings,” according to Yuval Noah Harari. Story is now so valued that, in many realms, it has become compulsory—consider the recitations required of asylum seekers or rape victims, who are penalized or dismissed if the parameters of their stories do not readily conform to the genre.”

Sehgal must be clairvoyant, I say this because at this point (in time) had the following conversation with myself, Me: What happens if story-telling lets us down? Does not deliver so to speak?

Alter Ego spoke to me as follows: Why not just continue reading the article? Perhaps you will find the answer.

Me: Great Idea!

So I did and there is it was, right before my very eyes, It shall now be right before your very eyes.

“And if a story betrays us? The solution, it seems, is to cast about for a better one. The journalist Nesrine Malik makes this case in the 2019 book “We Need New Stories”: “It is pointless to fight fake facts, or true but cynically twisted facts, with other facts. The new stories we need to tell are not just the corrections of old stories, they are visions.” Narrative Initiative, which is dedicated to “durable social change,” is one of a number of organizations devoted to such strategies; “impactful, enduring social change,” it holds, “moves at the speed of narrative.” Anyone in my line has every incentive to fall in step, to proclaim the supremacy of narrative, and then, modestly, to propose herself, as one professionally steeped in story, to be of some small use. Blame it on the cortisol, though: there’s no stanching the skepticism. How inconspicuously narrative winds around us, soft as fog; how efficiently it enables us to forget to look up and ask: What is it that story does not allow us to see?”

Quite brilliantly Shegal goes on to discuss the inherent dangers in story-telling, citing as an example the 2001 George W. Bush speaking of his Cabinet nominations. (I do readily admit that I feel joy when George W. Bush’s foibles are revealed and resisted. Remember the Iraq war, and those illusive weapons of mass destruction. The USA massively destroyed one million Iraqis).

Shegal quotes Amit Chaudhuri’s “Against Storytelling”, presented at a 2018 symposium. This coincided with globalization, he said, and the insistence of the special importance of storytelling to so-called minority communities (the demand that Indian writers, say, should “tell our own stories”) was a contrivance of “literary marketing.” It favored the creation of particular stories—spiced with “local” flavor and ready for export—and punished work that was formally challenging. If communities needed easily parsed stories in order to be heard, we were told, people needed them in order to heal. “My story has value,” the comedian Hannah Gadsby said in their Netflix special “Nanette,” describing their experiences of violence and misogyny. “Stories hold our cure.”

Shegal then speaks of the infectious spread of the ‘narrative’ – it has spread, like a cancer, it seems

“In the past quarter century, the narrative turn has spread to economics, law, and medicine. (Columbia established a Narrative Medicine program in 2001.) Increasingly, narrative has been a business strategy. Today, consultants regularly counsel that a “compelling brand story” is vital to a successful I.P.O. In “Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind” (2017),Christian Salmon traces the way corporations moved aggressively into storytelling, sometimes as a form of damage control. Campaigns against sweatshop labor—and images of Pakistani children hunched over, stitching together Nike soccer balls—incited consumer outrage. “

Shegal continues, and this blog will cite her powerful, adroit words and insights. Happening upon this article was music to my ears. (Music to my ears is an idiom, something you are pleased to hear about. It can also mean something that is soothing to your years; news that sounds pleasing to someone and becomes a source of happiness, a sound or words that bring amusement to us, something that we are willing to hear in order to attain happiness).

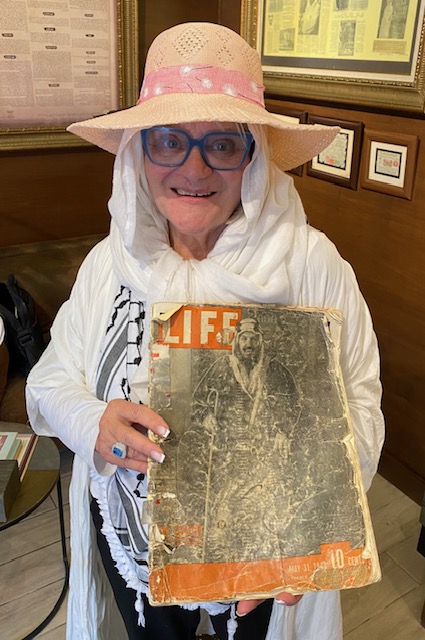

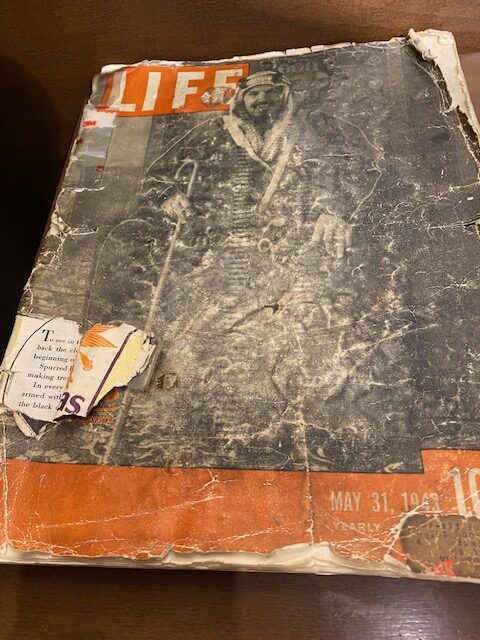

The article brought Sheer happiness as I have a story to tell, SUCH A STORY! It is the story of My Magazine, some details are enshrined in the Free Palestine menu selection of this blog. I shall tell the story, at a future time, in all of its complexities. But first you shall have the Happy Ending. During my Saudi Sojourn, not only did I find my magazine (or reasonable facsimiles of it) but also the identity of the culprit – the magazine thief. Discovered that man was not a Sultan, as represented, after all. He was (and is) a lawyer (of all things).

Photos will follow but you shall have to wait for the intrigue. My imminent move to Saudi Arabia is requiring much packing, decisions, leave-taking and concentration. Besides that the story has not as they say, played out. The conclusion will take place in Saudi Arabia. But the search has ended, my despair alleviated as Saudi Arabia has the story of its glorious past. PHEW.

The photos include a ‘selfe’ the photo requested by the magazine thief in September of 2021 in Dubai. A copy of the magazine under glass, a torn one found in the ‘library’ in Old Town Jeddah, and a photo of the magazine thief found on Google, dated 2018. He did not age well – with me on his tail he shall probably look most ancient. I think I know where he lives. My discovery of the two magazines were totally accidental, random, coincidental. Or were they????